Cyrus McCormick Revolutionized Farming Worldwide With The Reaper reaper machine

Cyrus McCormick did not invent the first mechanical grain reaper.

By the 1830s, farmers had already been tinkering for centuries with ways to improve on harvesting with the hand-held scythe, used by the 70% of Americans who worked in agriculture. It took one person 14 hours to cut and bundle an acre of wheat.

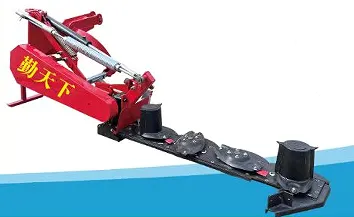

Walking tractor mounted reaper head

By 1840, McCormick had built on the experiments of others to come up with the first really effective horse-drawn reaper that got the time down to 90 minutes.

When hundreds of imitators came out with their own versions, McCormick crushed them with a total package no one could match, inventing modern product marketing in the process: quick delivery, reliable technology, fast service, installment payments and a money-back satisfaction guarantee.

“McCormick focused on the big picture of customers,” Christine Heinrichs, author of “The Backyard Field Guide to Chickens,” told IBD. “He was not simply interested in increasing profits quickly, but in dominating the market by making it risk-free to buy and essential to competitive productivity. His invention made farmers’ lives better, released workers for the industrial revolution and made the biggest contribution to ending hunger around the world.”

Virginia Rise

McCormick (1809-84) was born to a well-off family on 1,800 acres in Walnut Grove, Va. His father loved to invent things and tried many times to construct an effective reaper with the help of his eldest son, Cyrus.

Finally, he gave up and turned over the project in 1831, when Cyrus was 22.

He soon did his first demonstration in front of 75 neighbors, who saw that the reaper didn’t handle uneven ground well. In 1834, he still wasn’t satisfied with the reaper, but he heard someone else had taken out a patent for his version, so McCormick filed for his own.

The McCormicks decided that in order to earn enough money to manufacture it, they needed to start an iron mining and smelting business. That went well until the Panic of 1837, which nearly bankrupted them.

By 1839, they had paid their debts, and Cyrus began doing public demonstrations again. He sold his first two machines the next year for $110 each (equal to $3,100 now). They broke down, but he fixed the flaw and sold seven in 1841, while improving the product. He began using testimonials in ads, which brought in orders from all over, more than their workshop could handle.

It was also expensive to ship the half-ton contraption from the farm. It had to be hauled by wagon to a rail center 100 miles away, then taken to a port and transferred to a ship, which might sail to New Orleans and up the Mississippi River to the nearest city for the customer, finally delivered by wagon.

McCormick sought to solve this and the capacity problem by licensing others in different regions to make the reaper. In 1844, his factory made 50, with 25 manufactured by others.

“As demand grew steadily, he encountered a quality control problem,” wrote Daniel Gross in “Forbes’ Greatest Business Stories of All Time.” “Some couldn’t produce machines quickly enough to meet the market’s demand. Others balked at adding improvements. With eager customers ranging from upstate New York to the far side of the Mississippi River, the family realized that its business would suffer if it didn’t relocate closer to the new customers in the burgeoning West.”

Go West, Young Man

In 1847, McCormick moved the headquarters to the frontier town of Chicago, with the new factory expanding until two-story buildings covered 7,600 square feet. The company was initially a partnership with a former licensee, and in 1848 they turned out 500 reapers.

After a quarrel over management, the partner sold out to two hands-off investors, whom McCormick bought out for $65,000 (worth $2 million now) in 1849, when the factory turned out 1,500 machines.

“Chicago was a counterintuitive choice because it had only 17,000 residents and few paved streets,” said Chaim Rosenberg, author of "Yankee Colonies Across America.” "He saw the city's potential for shipping because of its location on Lake Michigan, connected by canals and channels to the Northwest and Northeast, as well as its future as a railway center, as grain poured in from the vast lands of the West and products were distributed to Western markets. McCormick and his descendants became major benefactors for Chicago higher education, built the vast McCormick Place Convention Center and owned the Chicago Tribune.”

In 1851, McCormick went to London to do competitive cutting with his reaper at the Crystal Palace Exhibition, the world’s first industrial fair, where he won a gold medal and stimulated initial European orders.

By 1856, his factory was making 4,000 reapers a year for domestic and foreign markets.

McCormick married Nettie Fowler in 1858, and she would bear seven children, the oldest being Cyrus Jr.

In later life, McCormick would rely heavily on her advice in important business decisions.

Constant Innovation

“Into the mid-50s, McCormick had made changes in the basic machine every year,” wrote Harold Evans, Gail Buckland and David Lefer in “They Made America.” “He sold improvements as a new model reaper, as auto manufacturers came to do. His wisest move, however, was to relinquish the role of inventor. … There was an acceleration in agricultural innovation that outpaced the creativity of any single inventor. McCormick stayed competitive by buying patents and companies and manufactured a revolution in marketing by guaranteeing one price for everyone and satisfaction guaranteed. He allowed installment payments: $30 down and the balance of $100 in six months after the harvest. In 1860, he was owed $1 million, charging 6% interest, the same as he paid.”

The Civil War, from 1861 to 1865, made McCormick’s machines mandatory for productivity. “The reaper is to the North what slavery is to the South,” declared Secretary of War Edwin Stanton. “By taking the place of regiments of young men in the Western harvest fields, it released them to do battle for the Union at the front and at the same time keeps up the supply of bread for the nation and its armies.”

In 1870, McCormick's factory turned out 10,000 machines. Disaster hit the next year with the Great Chicago Fire, which destroyed the factory and 2,000 machines that were being built, as well as a huge amount of material. The net loss, after an insurance payment of $250,000, was $1.1 million (equivalent to $22 million now).

McCormick saw it as an opportunity to build a larger factory with more advanced tools in a better location.

Final Years

In the late 1870s, thanks to improvements in transoceanic shipping and factory production, McCormick's company expanded into Australia, New Zealand and Argentina. In 1879, it produced and sold 19,000 machines and made a profit of $722,000 (equal to $17.7 million today).

But his brother Leander, who was managing the factor, strongly resisted increasing production, calling Cyrus’ plans “wild and visionary.”

Cyrus realized new operational management was needed to get to the next level. Exercising his ownership of three-quarters of the company, he fired Leander in April 1880. He renamed the firm McCormick Harvesting Machine Co. and hired Lewis Wilkinson, who had run plants for Colt’s Manufacturing, Connecticut Firearms and Wilson Sewing Machine.

“This brought an end to the blacksmith, machine shop, carpenter shop approach to reaper manufacturing and signaled the beginning of production under the American system of manufactures,” wrote David Hounshell in “From the American System to Mass Production.” “He immediately began operating the factory at night, and Cyrus Jr. served as his assistant superintendent and studied his work. Wilkinson taught young Cyrus the possibilities of special-purpose machines for large-scale manufacture. For the first time in the company’s records, the words 'gauges,' 'pattern machines' and 'jigs' constantly appear. Wilkinson could not effect many dramatic changes, but tried to bring more order and discipline to the work and workmen. Wilkinson remained with the company for only one year, but Cyrus Jr. succeeded him. In 1882, 46,000 machines were sold.”

Cyrus Sr. died two years later at age 75. His net worth was $11 million (equal to $274 million now).

Today, thanks to the revolution that McCormick jump-started, the less-than-5% of Americans who are now farming are able feed the world.

McCormick’s Keys

Made the first practical mechanical grain reaper.

Overcame: Strong resistance to new technology.

Lesson: Brainstorm every possible part of your product offering to make the package irresistible.

“Indomitable perseverance in a business, properly understood, always ensures ultimate success.”

Latest news

-

When to Upgrade Your Old Forage HarvesterNewsJun.05,2025

-

One Forage Harvester for All Your NeedsNewsJun.05,2025

-

Mastering the Grass Reaper MachineNewsJun.05,2025

-

How Small Farms Make Full Use of Wheat ReaperNewsJun.05,2025

-

Harvesting Wheat the Easy Way: Use a Mini Tractor ReaperNewsJun.05,2025

-

Growing Demand for the Mini Tractor Reaper in AsiaNewsJun.05,2025